Digital literacy and the digital divide

January 17th, 2022

Digital literacy and the digital divide

Are you digitally literate? Some days, when my computer fails to do what I want it to do, I personally feel quite ‘digitally illiterate”. Then I scream and want to hit my computer (which I never do in the end).

We are currently working on a digital literacy assignment for the Rwandan Ministry of ICT and RISA The project aims to help Rwandan citizens become more digitally literate so they can access digital services more independently. The project’s motto, “Leave no-one behind” is a great motto. Young ICT graduates work as digital ambassadors teaching people in rural areas how to use digital services like MoMo, EjoHeza (a pension scheme) and Irembo.

The key question when planning our work was: ‘When is someone digitally literate’?

Digital literacy in rural areas

We went to watch the digital ambassadors doing their training outside under the tree. Most villagers have feature phones and they can access services through codes. It’s basic, but it works. In rural areas, USSD technology does the trick.

We learned that a lot of people distrust digital services. How do you know if your money has moved? How to be sure you paid your water bill? If you have a shared phone, how can you find the SMS confirming you paid? The paper receipts we got in the past, felt safer. And, the water company may argue you didn’t pay.

The government goes digital

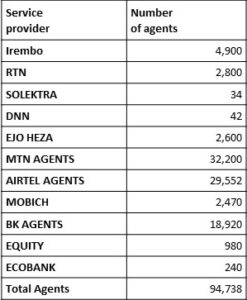

Rwanda is doing an amazing job of moving online official documents and permits that used to be issued by government offices and paid for at a bank. Examples include birth certificates, land registration documents, etc. Rwandan citizens can now save time: they don’t need to travel to government offices or banks. However, they do need a smartphone and an internet connection to access these digital services. A lot of Rwandans don’t have this, so they are dependent on agents. Being an agent these days is a profession: the table on the left shows agent numbers in Rwanda, with some agents having more than one role or function.

Rwanda is doing an amazing job of moving online official documents and permits that used to be issued by government offices and paid for at a bank. Examples include birth certificates, land registration documents, etc. Rwandan citizens can now save time: they don’t need to travel to government offices or banks. However, they do need a smartphone and an internet connection to access these digital services. A lot of Rwandans don’t have this, so they are dependent on agents. Being an agent these days is a profession: the table on the left shows agent numbers in Rwanda, with some agents having more than one role or function.

So, there are two major challenges – distrust and a lack of suitable devices. You can educate against distrust, but if people can’t afford the technology, then teaching them is pointless. They need to ‘learn-by-doing’ and practise what they are learning.

Based on our field observations, we suggested making simple materials like flipbooks so people can follow the instructions on their feature phones, and learn through guided practice.

However, we were asked to provide digital training materials, rather than paper-based flipbooks. Our materials will soon be available on Atingi.org. Atingi contains a range of different e-courses, al for free, but, you need to be quite digitally literate to follow the courses.

Teaching digital literacy

So, considering yourself to be ‘digitally literate’ is both a relevant and a relative concept. I need to work on Google spreadsheets without wanting to hit my computer. Someone else needs to learn to protect their phone with a pin, or learn how to save phone numbers and names properly.

One thing is for sure: the ‘digital divide’, the gap between the people who know and don’t know, is broad, and is a lot to do with the division between ‘the haves’ and ‘the have-nots’. A lack of knowledge or teaching materials are a smaller part of this divide.

My respects to the digital ambassadors for working hard to ‘leave no-one behind’.

Gerry van der Hulst